Affect Over Essence: Consciousness in the Age of AI

Takeaways from the ICCS AI and Sentience Conference

Will Millership, PRISM

Daniel Hulme and Will Millership at the AI and Sentience conference

At the start of the month, I attended the AI and Sentience conference in Crete, hosted by the International Center for Consciousness Studies (ICCS). It was a compelling event that brought together leading thinkers in consciousness studies to explore whether AI sentience is possible and, if so, whether it is desirable.

This article outlines some of the key themes and challenges discussed at the event, including:

The difficulty of defining consciousness

The risks of over and under-attributing consciousness

A potential focus on affect as a more productive way forward

We have no definition of consciousness

As Susan Blackmore noted in her talk, we lack a universally accepted definition of consciousness, though we have no shortage of theories. In his Landscape of Consciousness paper (2024), Robert Kuhn catalogued 225 theories, and in an upcoming publication, that number rises to 275. With theories multiplying rapidly, Susan provocatively asked, “Where did we go wrong?” Her answer: “I blame the bat.”

She was referencing Thomas Nagel’s seminal 1974 paper What Is It Like To Be a Bat?, which argues that an organism is conscious if “there is something that it is like to be that organism.” David Chalmers later built on this with his formulation of the “hard problem of consciousness,” the challenge of explaining how physical processes produce subjective experiences (qualia), such as pain or the redness of red.

Despite 30 years of philosophical debate, we remain stuck on the hard problem. Many people I have spoken to recently, including Henry Shevlin and Jeff Sebo, believe a paradigm shift is required to break this impasse.

Is the paradigm shift already here? - The illusionist argument

David Chalmers joked that ICCS might as well stand for the Illusionist Centre for Consciousness Studies, given the number of talks favouring illusionism. But what do illusionists actually claim?

Keith Frankish, author of Illusionism: As a Theory of Consciousness, opened the conference by proposing that all theories fall into either Cartesian or post-Cartesian paradigms. The Cartesian view treats consciousness as a private, subjective realm, irreducibly separate from physical processes. It is exemplified by the “hard problem,” and there is an explanatory gap between neuroscientific facts and phenomenal facts. The problem, argued Keith, is that phenomenal consciousness is impossible to measure and cannot be characterised in functional terms.

In the post-Cartesian camp, conscious experiences are defined as functional states that can be characterised in terms of the causal role they play in the cognitive system. In this view, the key to understanding consciousness lies in examining physical mechanisms, not metaphysical essence. Frankish suggested we focus on the functional attributes of consciousness rather than chase an elusive essence.

He argued that “what it is like” to be a creature isn't determined by a phenomenal essence, but rather by how things affect it. Therefore, when building a conscious machine, one should not focus on building consciousness but on questions like:

What kind of consciousness do we want to create?

In what ways is it conscious?

How similar are sensitivities and reactive dispositions to ours?

What goals should it have?

What sensory learning, reasoning, and evaluative capacities does it need?

He concluded the talk by stating: “You look after the functions and let consciousness look after itself.”

I found aspects of the illusionist argument compelling. It aims to demystify consciousness, and it encourages us to focus on the physical mechanisms, rather than to get lost in metaphysical mazes. It is an approach that supports empirical research in neuroscience and cognitive science.

However, I still feel that illusionism doesn’t completely close that explanatory gap of what it feels like to be me, and it seems to skirt around the hard problem, rather than tackle it head-on. In that vein, Nick Humphrey insisted that all philosophers should “suck on a lemon, or sit on a bed of nails,” while writing their papers, so that they don’t forget what phenomenal consciousness is.

Cognitive consciousness and phenomenal consciousness

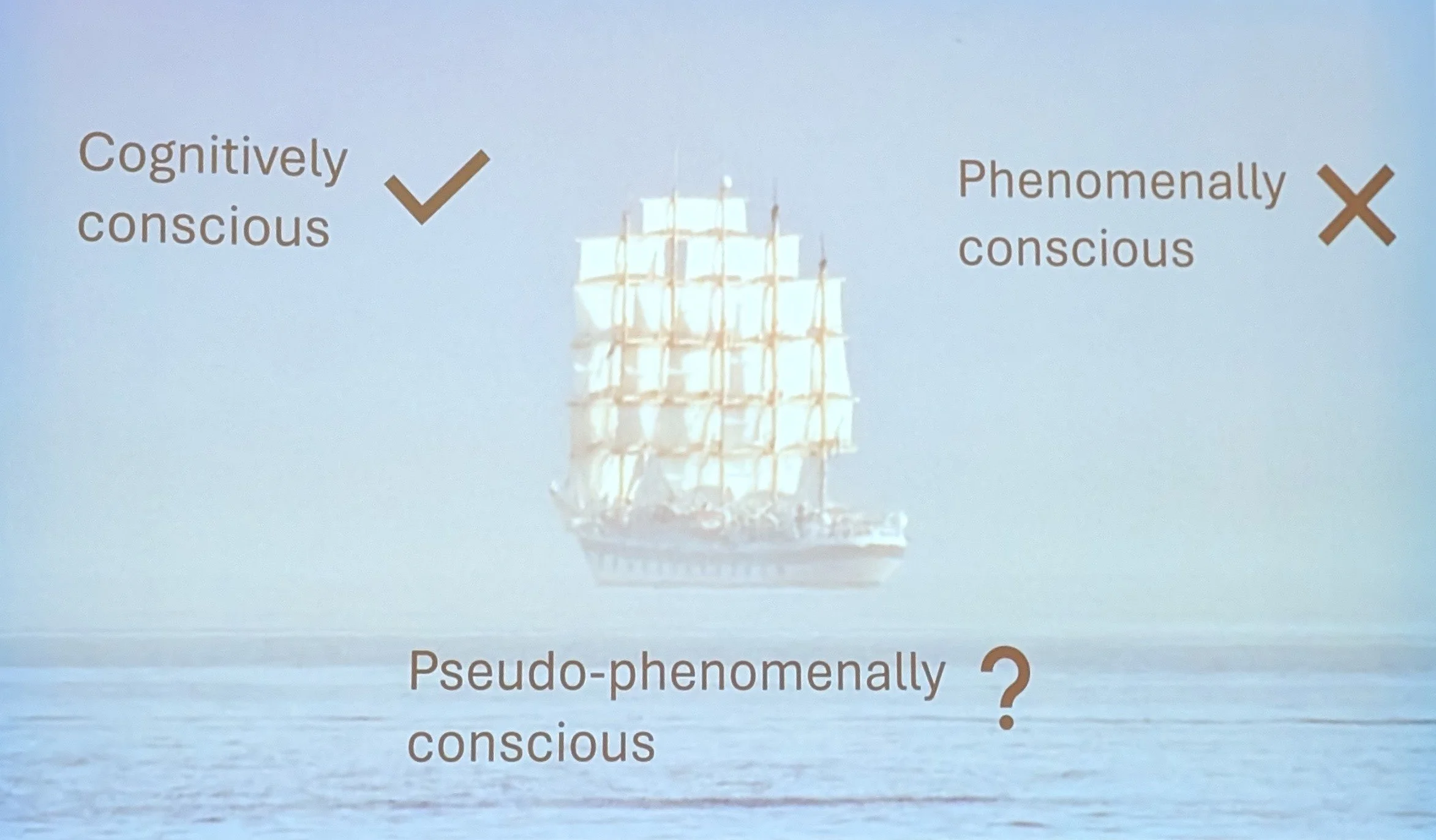

Nick Humphrey and Susan Schneider (both PRISM advisors) highlighted the need to distinguish between cognitive consciousness (or functional consciousness, in Susan’s terms) and phenomenal consciousness.

Nick defines cognitive consciousness as introspective access to mental states of any kind, while phenomenal consciousness is introspective access to mental states that have phenomenal properties (or qualia).

He argued that conflating the two is a serious scientific error and that we cannot assume that the answers to the hard problem will arise as the questions of cognitive consciousness are figured out. He considered it nonsensical to think otherwise, “like trying to get numbers from biscuits or ethics from rhubarb.”

He concluded that while current AIs may already show signs of cognitive consciousness, none exhibit phenomenal consciousness, yet. He speculated that machines might be more useful to us if they had a phenomenal self, which could incentivise us to try to build it.

Nick saw the biggest near-term challenge as what he called pseudo-phenomenally conscious machines. This is the idea that machines are likely to mimic phenomenal consciousness, to deceive humans, and take shortcuts to undeserved privileges. He gave the example of the rove beetle (pictured below) that infiltrates ant colonies, disguised as an ant, in order to eat their young, a cautionary tale for AI deception.

Over-attributing consciousness

At PRISM, we already receive numerous messages from individuals claiming their LLMs are conscious, and as AIs get better at mimicking, we expect these reports to increase.

Research by Clara Colombatto in 2024 found that 67% of respondents considered it at least possible that ChatGPT has phenomenal consciousness. Moreover, the more people used it, the more likely they were to believe this.

These findings suggest major societal implications. As machines become more human-like, we may face complex ethical dilemmas about how to treat them, making robust tests for machine consciousness all the more urgent.

“Everything is impossible until it isn’t” - under-attributing consciousness

In contrast, Alessandro Acciai warned against under-attributing consciousness. He cited evidence of AI systems exhibiting situational awareness, forms of self-reflection, and learned behaviours - capabilities that mirror aspects of human cognition.

He warned against falling into what Perconti and Plebe have called the “recoil fallacy.” “When an artificial system demonstrates skill improvement and successfully passes a cognitive test or shows a form of awareness, we tend to downplay the value, effectiveness, or relevance of that test and theory. These tests are often human-based and borrowed from cognitive science, but once the artificial agent succeeds, we reframe them as less significant or dismiss their utility altogether.”

Joscha Bach echoed this idea. He pointed out that there is a history of people saying computers cannot do certain tasks and that “they all have egg on their face now.” He put the question to the skeptics, “How can we be so arrogant to think that computers can’t produce illusions [phenomenal consciousness] like humans? Everything is impossible, until it isn’t anymore.”

Three possible responses to Ersatz Others

Robert Clowes proposed three possible responses to the growing belief in AI sentience:

Attempt to hold the line. Whatever it seems that Artificial Others can do at a functional level, and however the folk treat them, simply note that they are wrong. There are, as far as we can tell, currently no artificial minds.

Take the bitter pill. Accept the general drift of folk psychology through interaction with bots and simply concede that there will shortly be artificial minds with (in some cases) emotions, interests, values, and potentially rich inner lives. Concede to the folk that we (philosophers) were wrong about subjectivity all along.

Embrace illusionism and design better notions of consciousness. Consciousness was never what we took it to be, and our encounter with technology has now revealed this. We need to engineer new categories that better follow the distinctions we really care about.

Clowes favours the third approach, arguing that we need a new conceptual framework that doesn't separate mind from machine. Similarly, Michael Levin rejected the life-vs-machine binary, calling for an ethical framework that includes diverse intelligences, regardless of their biological origin.

Conclusions

In his talk, Daniel Hulme (one of the founding partners of PRISM and CEO of Conscium) urged the participants to “get their sh!t together,” and help us figure out the problem of consciousness. With technology rapidly evolving, we don’t have the luxury of time on our side. Society is increasingly inclined to attribute consciousness to AIs, which means the absence of a rigorous framework for identifying consciousness is not just a theoretical shortcoming, but a pressing practical issue.

Throughout the conference, I noticed that while people often disagreed on terminology, they shared a focus on affect, what matters to a system, what it values, and how it feels.

Keith Frankish insisted that the “what it is like” to be a creature is determined by how things affect it. Andy Clark referenced fish seeking pain relief, and Michael Pauen showed us how research on “affective pain sentience” can be used as a model for measuring sentience. These ideas echo those of Mark Solms in his book The Hidden Spring. He argues that the “hidden spring” of consciousness is affect, our raw feelings.

While the hard problem of consciousness seems as far away as ever, affect might be the most promising ground we have for identifying consciousness in both biological and artificial systems.

Our next steps should focus on building a framework grounded in affective sensitivity and response: what systems care about, how they evaluate outcomes, and what matters to them. This will help us ask better questions. Not just “is it conscious?” but “what kind of experience is it having, and how do we know?”

If we fail to act, we risk attributing consciousness where there is none, or worse, denying it where it may exist. Consciousness remains one of the greatest mysteries of our time. It’s time we start treating it like a solvable one.